Dr. Nune Chilingaryan

Yerevan State University of Architecture and Construction

ICOMOS Armenia

Vice-president on ICOMOS International Scientific Committee of 20th Century Heritage

The best examples of architecture built in multiple styles and geographical zones, have the features that unify them all: charged with the magnetism of the master-architect’s talent, they become the nucleus of great events enticing heroes of their time and ultimately absorbing the spirit and drama of their epoch.

Subsequently, they turn into the “radiators” of this mysterious energy. They convey memories and weave generations into the history, defining moral and cultural standing of the nation they belong to. In this context, securing the original shapes and uses of these buildings has an importance that goes beyond basic requirements for protecting art and architecture.

Hotel “Yerevan” became one of those unique examples for the capital city of Yerevan. By putting together and analyzing all the notions behind the creation of the hotel “Yerevan” it becomes clear that its important role of the resurgent Armenia’s urban, social and cultural realm has been predestined.

- Hotel “Yerevan” (former hotel “Intourist”) was designed by the talented Armenian architect Nikoghayos Buniatian who was the first chief architect of Soviet Yerevan.

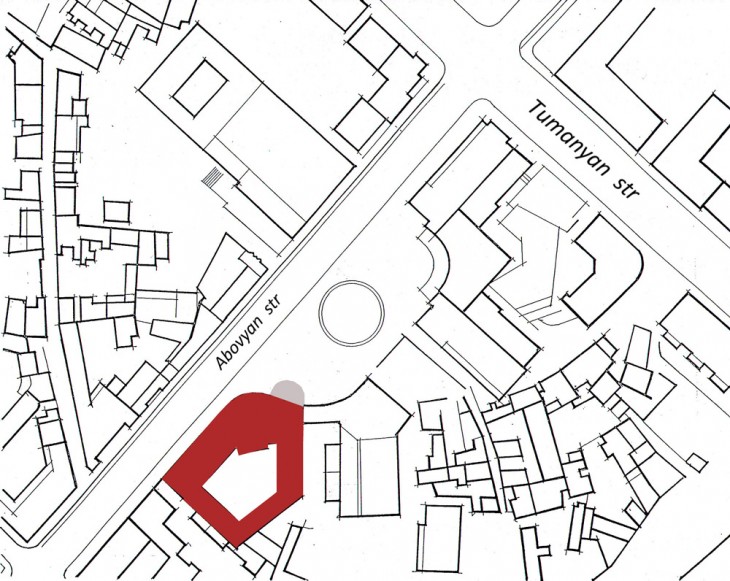

- It is located on Abovyan street (former “Astafyan” street), which was considered the main street in Yerevan (then known as Erivan), during pre-Soviet period.

- The hotel built in 1926-1928 was the first public building designed within the first master plan of Soviet Yerevan. Long before Yerevan’s Republic and Freedom squares were built, the curvy form of hotel “Yerevan” was already dominating the semicircular square today named after Charles Aznavour, a famous French-Armenian singer.

- And last but not least, the design of this officially first hotel in Soviet Yerevan was the first peculiar interpretation of the 17th century French Renaissance architecture.

There are not as many buildings in Yerevan (or in any other city) like hotel “Yerevan”, when briefly describing them one uses the words “first” and “main” numerous times. Built in a style that was unfamiliar to early 20th century Yerevan undergoing difficult times, this masterpiece set the standards for the future architectural square design, as well as greatly influenced developing a new lifestyle. Very quickly it became a ground for pivotal events; a meeting venue for prominent representatives of cultural “intelligentsia”, and simply a home for some famous Armenian artists. The walls of hotel “Yerevan” remember intense discussions on art and politics, joy and sufferings on the faces of famous Armenian writers such as Yeghishe Charents, Gurgen Mahari, Shirvanzade, William Saroyan, Hovhannes Shiraz, painters Ara Sarkissian, Panos Terlemezyan, Yervand Kochar, Minas Avetisyan, actors Vahram Papazian, Hrachya Nersisyan, David Malyan, Mher Mkrtchyan, Karen Janibekyan, and a director Sergei Parajanov (fig.1.).

1999. The year of renewal

The first decade of independent Republic of Armenia was the time of crisis for its people who fought for its independence since centuries. There were earthquake, war and blackouts, economic downturn, thousands of Armenians fleeing from a neighboring, former ally country to save their lives. It seemed unreal for Armenian people to overcome the crisis. And once again, like seventy years ago, hotel “Yerevan” became the herald of hope and renewal. Hotel “Yerevan” was the first public building to be restored in Yerevan, in the city that was coming back to life after the conflicts in early nineties.

On 1999 the hotel was purchased by one of the first international companies investing in Armenia’s economy, an Italian construction company “RENCO”. Hotel “Yerevan” has been chosen first of all due to its “European” appearance, which corresponded to that could be called a European landmark. The building maintained its architectural integrity despite of being physically worn out. It was necessary to give a new life to it; to upgrade the rooms and facilities to contemporary needs yet maintaining the building’s architectural image and essence.

The project was fast-paced. It was one of the rare cases when taking measurements, designing and implementation took place one after the other, almost simultaneously (Nune Chilingaryan, lead architect of the renovation,“KHORAN” architectural studio). In order to get the best results it was essential to apprehend and appreciate the architect’s motives and aesthetic principles for the hotel design. In order to renovate and to modernize a building like hotel “Yerevan” it was not enough to merely preserve and recreate interiors and exteriors. It was an attempt to understand the logic behind the overall composition of the building. While keeping in mind the architect’s vision and working with his ideas, it was important to carefully design new programs, to create an independent whole yet open it up to the urban environment.

Hotel “Yerevan” has an irregular pentagonal shape with inner courtyard. The building is interesting in its multi-functionality. This hotel is not merely a collection of rooms and facilities. While the hotel provides comfort to its visitors inside, one could see that it belongs to the city outside, and is a full participant of its environment. Hotel “Yerevan” is a vivid example of so called “urban architecture” which is well articulated in its plan and facades: the building has three main facades out of five that are overlooking Abovyan street, the semi-circular square and currently non-existent Mosque street (fig.2.). All the three facades are rich with architectural elements (balconies, loggias, arcades, window frames) decorating the main entrance, storefronts, restaurants, as well as the windows of luxurious rooms on the second and third floors. The other two bare facades overlook the courtyard of one of the city’s ordinary neighborhoods.

The facades are standing out with their elegant blend of colors and textures. The surfaces of brick-colored plaster are in contrast with black tuff and grey basalt of window surrounds and balconies.

The corner of Aznavour Square and Abovyan Street is the building’s most outstanding part. The interior of this four-storey-high corner accommodates building’s grand spaces: the oval shaped entrance hall with dynamic staircase and two magnificent halls on the third and fourth floors (Fig.3.). Compliant with the rules of classical architecture the hotel “exhibits its inner beauty outward”. Hence, the corner façade of the building greatly differs from its side facades (Fig.4.). Its first floor is entirely faced with basalt masonry. The loggia with ionic colonnade rises above the main entrance. And finally, the exquisitely designed balcony completes the façade of corner part.

During restoration works many elements of both interior and exterior, particularly the surrounds of doors and windows, column bases and baluster of the main staircase, were severely damaged. In order to restore them the skills of a goldsmith are needed. Therefore, only highly qualified craftsmen previously working on Hovhannavanq (one of the gems of Armenian medieval architecture) were entrusted to recover those elements (Fig.5.6).

The cantilevering balconies of the rooms were built of grey cement resembling basalt stone, the balusters of which were extremely worn out. Given the building’s architectural style, it was assumed that the balusters were supposed to be carved out of basalt stone, however considering Armenia’s economic hardship back in 1920s they were realized by cheaper, similarly attractive but unfortunately short-lived material – cement. During the restoration all the balusters were successfully replaced with basalt ones.

Difficulties emerged when recovering the original plaster of the building. Although during seventy years of its existence hotel “Yerevan” has never been substantially renovated, however the exterior as well as the interior walls of the building have been repainted several times. By 1999 the hotel has acquired a reddish-brown hue which was far from the original color. The only façade that was left untouched and preserved its original color was the one overlooking currently non-existent Mosque Street. It used to be one of the main facades that had been forgotten inside the courtyard of its adjacent building of Artists’ Union of Armenia constructed later during 1950s. It turned out that Buniatian had come up with an interesting technology when applying color to the building. The so called plaster-paint consisted of tuff dust, pigmentation of which resulted in rich brick color. In 1999 in Armenia it was impossible to recreate similar type of plaster, the decision was made to order plaster from abroad, from “Giolli” manufacturing company in the city of Fano, Italy. Based on results of chemical analysis of the original plaster a new mixture of plaster has been produced which was very close to the original one.

Very often renovators were forced to “guess” Buniatian’s design intents since some important elements were simply missing. So, like the interior doors of the entry hall, some other elements were being redesigned from scratch in accordance with hotel’s style.

It is a big responsibility to renovate a functioning, “active” landmark. And sometimes making certain changes becomes inevitable. The level of professionalism of the authentic building appears as an indicator of innovative qualities serving as a litmus test: successful new design approaches harmoniously blend in with the whole, while failures dramatically stand out maintaining their strange look and artificialness over the time. Turning the inner courtyard into the glazed atrium was a successful implementation as it seemed to further carry on author’s idea of having an internal space for more cozy and intimate communications. Today it became a beloved recreation space for the hotel’s visitors. As opposed to the atrium, turning the existing summer café into the restaurant extension (built after the completion of renovation works by the initiative of “RENCO” administration) was a failed attempt from architectural, urban and historical point of views. The extension disturbs the rhythm of the continuous arcade, distorts the look of the main façade and breaks the semi-circular delineation of Aznavour square (Fig.7). As a result, the building and the square have lost the power of enticing, and “the magic of the place” has been vanished. Let us not forget that it was place where the most brilliant representatives of Armenian bohemia would gather…

Famous novelist Jacques Lamarche once said: “It is impossible to build future on memories and sacrifices, no matter how beautiful they are”. This might be true when talking about futures of human beings. However, the immense experience of building gained in the course of time proves the opposite: the cities carrying memories of past generations happen to be the most resilient and thriving. The buildings that overcame difficulties and survived throughout the time are the most abiding and attractive. Hotel “Yerevan” is one of them as long as it carries its memories into the future.

|

Heritage Conservation Regional Network Journal

|

|

Introducing_Young_People_to_the_Protection_of_Heritage_Sites ENG

Details »

|

|

Networking |

Policies |

|

|

Public awareness |

Workshops |

|

The project is funded by the

The project is funded by the European Union

EU is not responsible

for the content of this website

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RCCHD Project: Office 16b, Betlemi ascent, 0105 Tbilisi, Georgia Tel.: +995 32 2-98-45-27 E-mail: rcchd@icomos.org.ge |

© 2012 - Eastern Partnership Culture Programme |