Prof. Olena OLIYNYK,

vice-president of National Union of Architects of Ukraine, Ph. D.

When I was doing postgraduate training in the United States in 1996, I had the honor to speak about Ukrainian architecture before a small professional audience in Harvard. Then I had to start my presentation as follows: “Ukraine is a European country with a population of more than 50 million. Its capital is Kyiv.” All that most Americans knew about Ukraine at the time was Chernobyl. Recently, the situation has changed. The heroic and tragic events of last winter finally put Ukraine on the map, as the cliché goes.

The Ukrainians have demonstrated an extraordinary strength of spirit, continuing peaceful protests for more than three months. They ousted a corrupt gangster regime and re-established the independence of our country after 23 years as a technically independent post-Soviet state.

We have lost more than a hundred young men and women – university students, teachers, farmers, businessmen, and factory workers. They were unarmed. Most of them were killed by snipers.

The Ukrainians have named their fallen heroes “Heaven’s Hundred” – an army that will continue to defend our freedom and independence even in Heaven.

The epicenter of all large-scale radical protests in modern Ukraine has been Kyiv’s central square called Maidan Nezalezhnosti – Independence Square. Ten years ago, during the Orange Revolution of 2004, the Ukrainians stood their ground on the Maidan after rigged elections. More recent events, which rallied the nation even more, have made Maidan a generic name synonymous with freedom and dignity.

The architectural history of the place is no less dramatic, and the distinctive features of its spatial solutions and its relationship with the relief of downtown Kiev have played a central role in the organizing of mass rallies and the formation of the Ukrainian national identity.

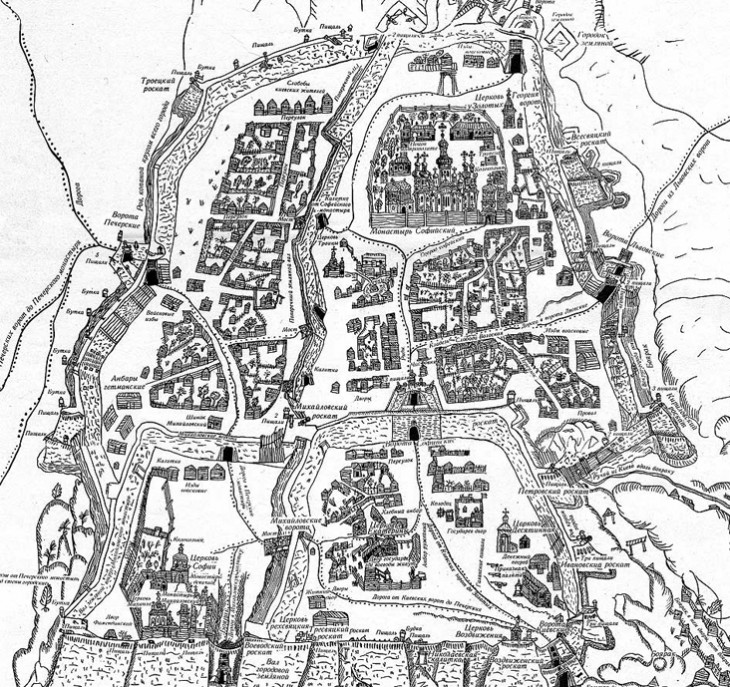

Historically, Kyiv had two central squares. Initially, the city’s administrative center was located on its highest hill in the Upper Town, within the limits of the so-called city of Prince Vladimir, and later Prince Yaroslav. Kyiv Rus was one of the largest and most developed European countries in the 10th-13th centuries.

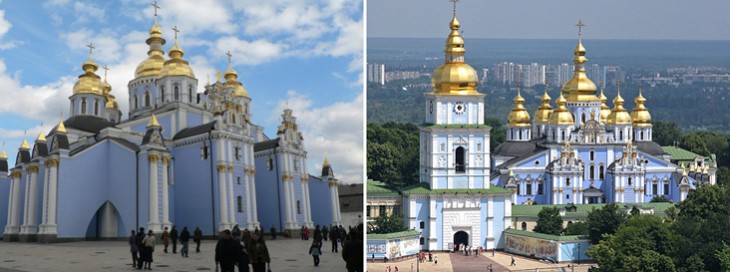

Yaroslav the Wise established close ties with Byzantium and Western Europe in the first half of the 11th century. He built the main church of Kyivan Rus – St. Sophia Cathedral – on the model of Hagia Sophia of Constantinople. The axis connecting St. Sophia and St. Michael’s cathedral, which was erected half a century later, formed the main square of the city, its administrative and political center. In 1240, Kyiv Rus, one of the largest European countries, was burned down and looted by Khan Batu and could not regain its significance for over 300 years. You can see the ruins of the Golden Gate and the Church of the Tithes, the first Christian church of Kyiv Rus.

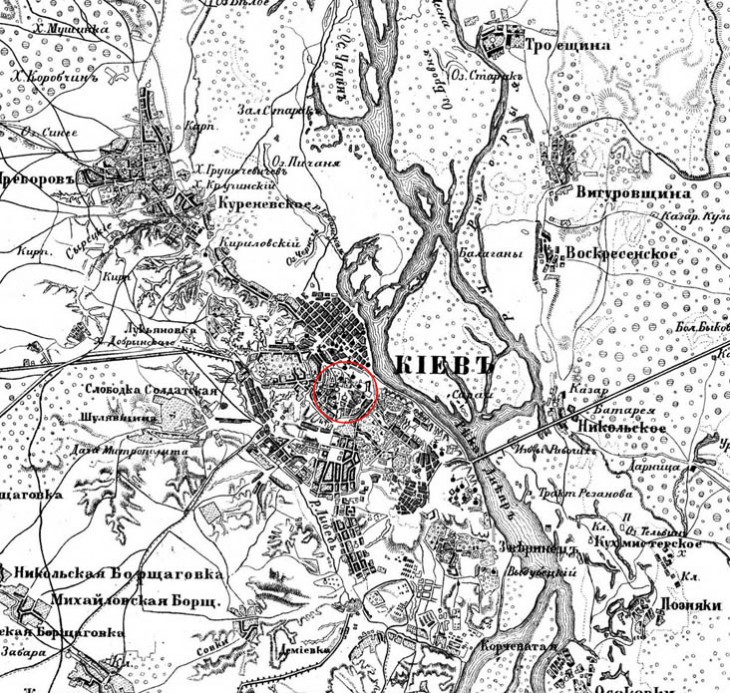

In the 17th and 18th centuries, during the heyday of Ukrainian Baroque, ancient shrines were restored and decorated and the lower, the valley part of Kyiv called Podil was settled. Actually, it was a separate town linked with the Upper, the Princely City by what is now called St. Andrew’s Descent; Khreshchatyk, the city’s main street today, remained a boggy creek called Goat’s Swamp until the late 18th century. It was there that the fortifications of the Upper City began, but they had been destroyed during the Mongol invasion and almost completely dismantled by the early 19th century. It was not after their ruins were pulled down to clear the place that a square was formed at the foot of Old Kyiv Hill, right next to the Khreshchatyk, which was soon built up and later received the status of the city’s main street.

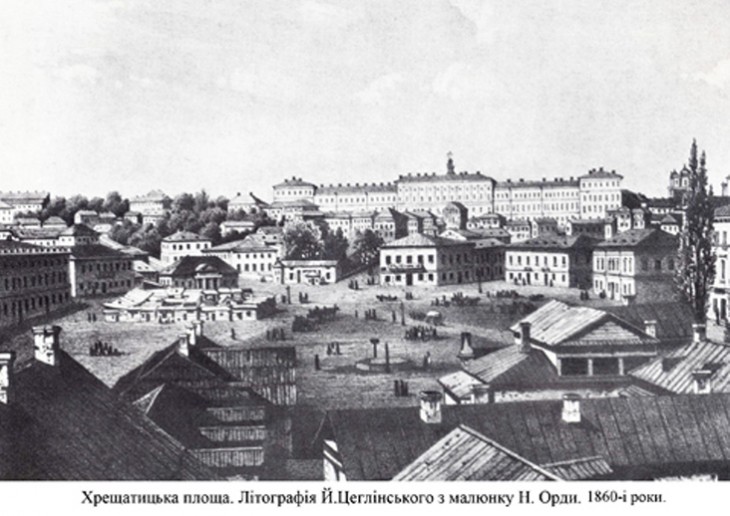

The history of Independence Square began in the first half of the 19th century. In 1830s, the first wooden houses were put up along its perimeter. In the 1850s, they made way for the first stone structures, including the building of the Noble Assembly by architect Alexander Beretti. At the time, the square housed a permanent market and hosted open-air fêtes on major holidays. Hence the square’s first name, Bazarna. There is a mention of circus performances by traveling shows – which must be why the city’s first stationary circus was built right off the square, on what is now Horodetsky street.

Gradually, the square was built up with all types of shops, inns and taverns. In 1869-1876, it got the name of Khreshchatytska after the Khreshatyk Ravine around it. When the City Assembly, or Duma, was built there by architect Alexander Schille, the square was renamed Dumska.

Dumska Square was not unlike a forum of Antiquity and Renaissance in that it was designed for public gatherings and isolated from the city’s thoroughfares. Historically, a dense ring of buildings were built in squares like that, or they were surrounded by arcades, or located on the crossing of secondary streets – lines of pedestrian flows.

The building of the Duma was put up along the building line of Khreshchatyk, so the square found itself to the rear of the horseshoe-like structure and formed an enclosed space with a public fountain as its centerpiece. In fact, it was a small-town square for leisurely strolls, gatherings, and recreation. The city’s main square continued to be on the top of Old Kyiv Hill, in front of St. Sophia Cathedral.

In 1913, a bronze monument to Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin, who was assassinated while on a visit to Kyiv, was erected at the entrance of the Duma. When the Bolsheviks took hold of the city in 1919, they pulled down the monument and renamed the square Sovetskaya.

The Bolsheviks moved the capital of Ukraine to Kharkiv near the eastern border with Russia because the struggle for independence did not end in Kyiv until 1920. Stalin punished Ukraine cruelly for her desire to be free. A series of mass reprisals, designed to eliminate the more disobedient part of the population of Central Ukraine and re-settle or “pacify” the rest, was crowned by the artificial famine of the early 1930s known as Holodomor. Ukraine underwent the greatest hardship throughout Stalin’s purges with their nationwide toll of 40 million people destroyed or thrown in hard labor camps.

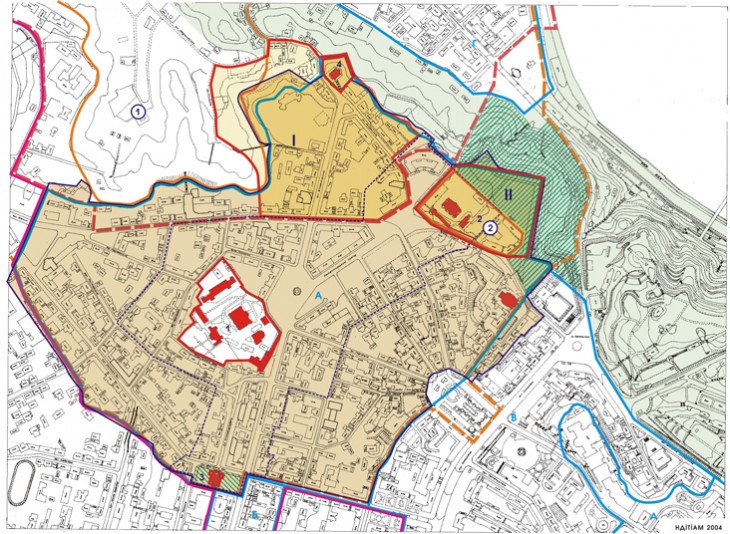

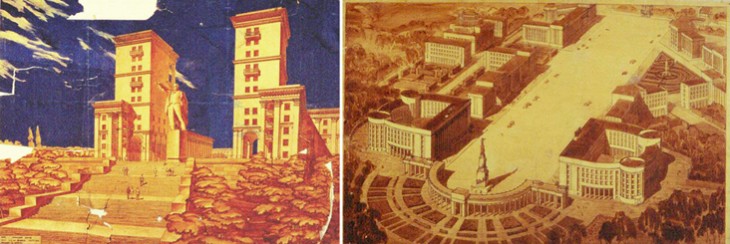

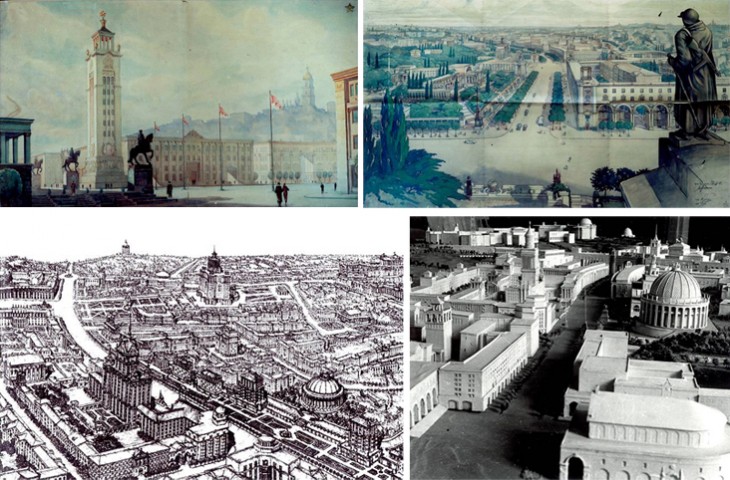

In 1934, the Bolsheviks made Kyiv the seat of the government of Soviet Ukraine again, for which purpose they developed a plan for the construction of a government center at the top of Old Kyiv Hill, near St. Sophia Cathedral. 12th century St. Michael’s Gold-Domed Monastery was demolished. St. Sophia and the 19th-century Government Offices complex were to be blown up too, but the Second World War interfered with those mad plans. An All-Union competition in 1932-34 defined the concept of the Government Center: the main axis that used to unite St. Sophia and St. Michael was to be expanded and turned into a square fit for military parades, with an enormous statue of Stalin completing the pompous esplanade. While the architecture of the buildings to line that vast “parade ground” differed from one another in design, the idea behind all of them was the same. The winning design by Iosif Langbard was approved for implementation, but only a part of the complex was built. That is the present Ministry of Foreign Affairs building with its colonnade not unlike the temple complexes of Ancient Egypt with their mammoth proportions.

The Dumska, later Soviet, Square acquired its almost present appearance in the interwar period. With its front opening on Khreshchatyk’s red line, the former Duma building housed the regional committee of the Communist Party, but still had in its rear a public square with a fountain around which a streetcar looped. Until 1941, the odd-numbers side of Khreshchatyk was built up with a sheer row of residential buildings, with the 14-storeyed Ginzburg boarding house, the city’s tallest building, looming where the Ukraina Hotel stands now.

The Ginzburg house, the former Duma building and almost every large structure on Khreshchatyk were blown up by Soviet underground fighters and destroyed in massive fires during the first few months of Nazi occupation in autumn 1941.

A competition for the reconstruction of Khreshchatyk was announced in June 1944, almost a year before the end of the war. All leading Soviet architects took part. No doubt, most of the designs were in the mainstream of the “historic” trends of Stalinist architecture of the period. And yet even those designs proposed a totally new scale of the city’s main street. The building area on the odd side was moved towards the hill, with a pedestrian boulevard being formed in front of it. Naturally, triumphal arches, monuments, towers and parade grounds for squares were indispensable attributes of all designs.

Two teams were admitted to the second round – those headed by Alexander Vlasov and A. Tatsiy. However, the master plan of Khreshchatyk was not signed into execution until 1949, and its implementation was imposed on Kyiv architects, among them Anatoliy Dobrovolsky, Viktor Yelizarov and Olexandr Malynovsky. They were instrumental in using the competition designs to the best of advantage. The main thing which they succeeded to do was to give the city a new scale that the capital of Ukraine deserved, to accentuate the unique landscape of central Kyiv with the main building line and even translate certain allusions of Ukrainian Baroque into stone in the curly rooftops of the facades.

Khreshchatyk’s new appearance had enormous influence on the development of architecture in the former Soviet Union. It still remains one of the best works of the so called totalitarian architecture. From the town planning perspective, it is an integral architectural ensemble 1200 meters long and an average of 75 meters wide, with three squares, broad sidewalks, and buildings from various periods. In my own opinion, nothing better was built in all the subsequent decades.

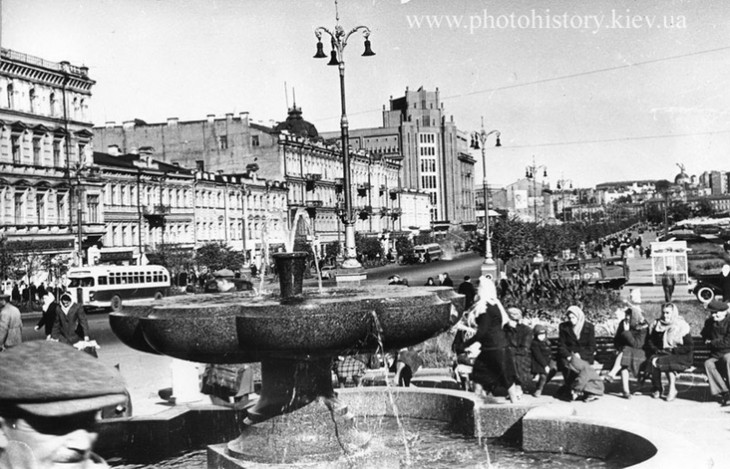

The space of the main square – now named Kalinin Square for a statesman in Stalin’s government – was changed too. After the debris of the blown-up Duma building was cleared up, the space of the square opened on Khreshchatyk. On the opposite, odd-number side, the square was expanded as a cascading parade staircase in front of the Moskva Hotel (now Hotel Ukraina). The prewar fountain in the center of the square was preserved. Intact two- and three-story buildings around the perimeter survived well into the 1970s.

After the reconstruction was finally completed in 1977, the square got its new name – the October Revolution Square.

The new spatial concept confirmed the semantic value of the Revolution Square as the city’s main parade ground. The space of the square was expanded to include the opposite side of Khreshchatyk and “demarcated” with an impressive monument – a statue of Lenin surrounded by revolutionary workers. For all its Communist ideology, the composition of the square as a focus of urban space was immaculate. By far the best town-planning solution ever, it combined parade, government and social functions, featured a rebuilt fountain, and quickly became the Kyivans’ favorite recreation area.

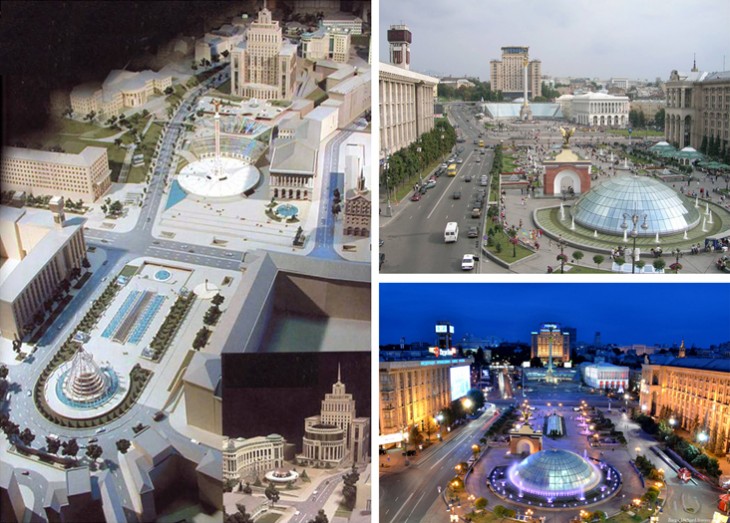

Shortly after the independence, however, it became clear to the conservative post-Soviet government of Leonid Kuchma (1994-2004) that the excessively open space of the square accommodated too many people. Following mass student protests in 2000, Kuchma initiated a new reconstruction of the now Independence Square. In addition to the political goal of making the square as unfit for mass manifestations as possible, the burgeoning oligarchic interests wanted it fragmented into smaller areas so they could have sites for lucrative projects in the very center of Kyiv. Those were subterranean shopping malls, which quickly filled all the space under Khreshchatyk and the Independence Square. That decision forever buried the chance of making Khreshchatyk a two-level thoroughfare with underground parking lots and turned the Maidan into a chaotically built-up exposition ground of various clan identities.

On the one hand, patriotic Soviet symbols made way for the domes of underground shopping centers. On the other, spaces in between those composition accents were filled in with all kinds of purely decorative and largely tasteless representations of the new identity such as the sculptures of the city’s patron Archangel Michael, the legendary founders of Kyiv and the Cossack Mamai as the mythical national hero, the Polish Gate rebuilt in an unabashedly kitsch baroque style and, finally, the Independence Column topped with an ethnographic maiden in folk garb. As a result, the visual relation of the square to the general space of the city was lost, and the Maidan was cluttered up with structures of various heights. Instead of the neatly organized and clearly delimitated functions of festive manifestation and informal recreation, the square turned into a hodgepodge of sundry spaces. The Kyivans’ favorite fountain was dismantled, festive manifestations were to move out to Khreshchatyk, and commercial buildings became the ideological manifesto of the new authorities.

The outburst of popular resentment in 2004 known as the Orange Revolution and the advent to power of the initially democratic government of Yushchenko-Tymoshenko seemed to give a fresh impetus to the lookout for a new identity. In architecture, however, it boiled down to a wave of reconstruction of churches destroyed in the Soviet period and lavish ornamentation of high-rise buildings with fake Ukrainian baroque elements. In essence, instead of supporting the national idea through architecture and urban planning, the corrupt oligarchic elite flirted with the people, donning Ukrainian attire for greater patriotism.

When the openly pro-Russian gangster regime of President Yanukovych secured its hold on Kyiv, it stopped even flirting. As a result, the past eight or nine years have given the historic appearance of Kyiv the hardest blow ever, destroying the integrity of its urban configuration, eliminating its beautiful vistas, and turning its center into an ugly, amorphous clot of substandard high-rise architecture without even a try at esthetics.

In addition to the gigantic shopping malls which occupied the city’s squares and other open spaces, the greatest share of investment in construction went to high-rise residential and office blocks. All possible norms of height and density were violated thoughtlessly. The result brings to mind the cities of underdeveloped postcolonial countries with their facelessly universal, “globalist” look. It has no claim whatsoever to engineering or artistic merit. In some cases, as if in mockery of the national idea, these garish high-rises are bedecked with ornate pseudo-Baroque and Classical décor.

On the one hand, Kyiv’s recent architecture is marked by pointed internationalism, purposeful neglect of the city’s heritage, and growing congestion as a result of high-rise construction in the historic core and erasure of open public spaces from the city map. On the other hand, pseudo-historic fakes in architecture and décor continue to dominate the scene.

While the reconstruction of lost historic and cultural monuments started out in the 1990s with the aim of reviving the Ukrainian national mythology, it acquired absolutely incredible forms in a combination with the thoroughly corrupt, gangster-like construction practices of the 2000s, giving rise to mass production of fakes and clones and substituting an imaginary history for the true one.

The independence, which Ukraine obtained so unexpectedly and so easily in 1991, has never been reflected in its architecture. In his fundamental study National Identity in Urban Architecture, Bohdan Cherkes, Doctor of Architecture, Director of the Institute of Architecture in Lviv, concludes that in the twenty-odd years of its independence, the Ukrainians have not been able to create a united mythology, an integrated heroic imagery that is necessary for the consolidation of any nation. In the western and eastern parts of Ukraine, national awareness developed along different paths, so apart from the heroic pages of the recent Soviet past and, partly, the ancient epic tradition those two parts of one country have never identified what they have in common in Ukraine’s millennial history. Ukraine was desperately lacking an inspiring modern history to unify all its lands.

National identity is the key component of any state’s national idea and the state itself. A new identity may be born within a nation as a result of political change or be imposed on it from without. All these years, Ukraine has been professing a kind of dualism. While the Ukrainians became increasingly aware of themselves as an independent nation, they still preserved a certain dependence on the deeply entrenched Soviet imperial attitudes and close ties with Russia. On top of that, the oligarchic, gangster type of capitalism exploited these sentiments skillfully, aiming to eradicate patriotism and enslave the people.

In architecture, features of identity manifest themselves in the formation of the main public spaces and the appearance of built-up areas. In public spaces, a new identity is shaped by town-planning, architectural, artistic and figurative means. Town-planning tools create a new volumetric-spatial layout system of the main public space and its composition, which is normally an axial one, with a clear hierarchy of spaces and a pronounced new ideological center in the form of a centerpiece structure – a symbol and a monument. Architectural input includes buildings that symbolize the achievements and explain the goals of the new political regime. In this case, special attention is paid to the function and style of the building. Finally, artistic and figurative means of asserting an identity include various monuments and small forms of ideological significance.

The public space of Kyiv’s main square was created in the Soviet era, while its architectural appearance was gradually supplemented in various periods. In the years of independence, however, the square and the city as a whole have not received a major work of architecture to reflect the idea of national identity at all. The main public spaces were only decorated with new imagery and artwork, which seemed to emphasize their temporary character.

This is why the main objective of Ukrainian people at the moment is to assert its own identity and create its own imagery. To quote Bohdan Cherkes, by identifying ourselves with the nation we do more than identify with our profession or community; this is a means of achieving personal immortality through common ancestors. Traditional values and myths of a nation are reflected in its culture, including architecture, and so they influence the consciousness of the public and the individual. Therefore, public zones of the capital of a democratic country should be transformed to emphasize its democratic character and perform other socially important functions.

At the moment, the numerous minor elements and sundry spaces on the Maidan of Independence interfere with its perception as an integral whole, destroying the visual image and feeling of the nation’s unity. The Maidan is overwhelmed with conflicting energies today. This architectural appearance of the nation’s main square gives rise to separatism and uncertainty in the minds of people.

The visual image of the Independence Square and the Maidan as a catchword have become a symbol of the just struggles of a nation and its self-identification process. Now it is up to architects to underline its meaning with architectural means. A powerful unifying element, perhaps a circle – for solar energy, growth and unity – should become the symbol of the Maidan instead of the domes of underground trade centers. It may well be that the Kyivans’ favorite fountain will return and assume its old place, making it the point of democratic social attraction.

For the time being, we cannot predict the fate of the country and its main public place with certainty. Yet, without a doubt, the Maidan’s architecture should personify the nation’s striving for freedom, democracy, and national unity as its hard-earned identity.

|

Heritage Conservation Regional Network Journal

|

|

Introducing_Young_People_to_the_Protection_of_Heritage_Sites ENG

Details »

|

|

Networking |

Policies |

|

|

Public awareness |

Workshops |

|

The project is funded by the

The project is funded by the European Union

EU is not responsible

for the content of this website

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RCCHD Project: Office 16b, Betlemi ascent, 0105 Tbilisi, Georgia Tel.: +995 32 2-98-45-27 E-mail: rcchd@icomos.org.ge |

© 2012 - Eastern Partnership Culture Programme |